Why do racial stereotypes persist when it comes to sex?

"Welcome to the Black Man’s Fan Club – a monthly swingers’ night for white women who want to have sex with black men, and their white husbands or partners who want to watch. In the ethnically undiverse world of swingers, the BMFC is marketed as a community of people who “appreciate the extras black men bring”. Tonight’s flyer features an intensely fake-tanned white girl wearing briefs that read, in large letters across her crotch, “I heart black”. Members of the community – both white women and black men – are active on Twitter, where they share pictures of exceptionally large black penises and rough sex in which a black man clearly dominates.

BMFC, the punters tell me, is one of a kind, but the sentiment doesn’t end in Dunstable. In an era of mass porn consumption, black male porn actors having sex with white women is a popular subgenre, and BMWW (black man white woman) erotic novels specifically cater to the fantasy of crudely stereotyped black male aggression and sexual domination. It’s as if the online commercialisation of sexual fantasy has globalised racial stereotypes and sent them freewheeling backwards; it doesn’t take any imagination to surmise exactly what swingers mean when they say they appreciate the “extras” black men bring.

“There are three reasons why the women come here,” explains Wayne, one of the black men who are here to be “appreciated”. Wayne has just come out of a playroom, and has barely bothered to put his clothes back on – his flies low, shirt open, and tie hung nonchalantly around his neck. He’s a good-looking guy, with a toned physique and neatly twisted locks. “One [reason is], black men have bigger penises.” That’s a stereotype, I argue. “It’s not a stereotype!” he replies. “Black men are built differently. You have to acknowledge nature. Number two,” Wayne continues, “black men have better rhythm in bed. That’s also a fact. And thirdly, they are just more dominant. You know, a lot of these women are not satisfied by their husbands, who want them to do all the work. They want to feel a strong man inside them, dominating them. They want an alpha male. That’s what they get here,” he smiles at me, knowingly.

[...]

When I ask if they feel fetishised because of their race, they vigorously deny it. “I come for the sex,” Wayne says. “Where else can you go and have sex as many times as you like? Plus, there are no pretences. Everyone is here to get laid, have a good time, it’s really friendly. It’s not like a normal club where everyone has a poker face on. No one’s judging.”

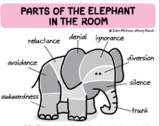

Swinging is not my thing, but I couldn’t care less what consenting adults get up to behind closed doors. It’s not the sex at the Black Man’s Fan Club that bothers me, it’s the racial stereotyping. It feels as if it’s just the latest chapter in a history of sexual stereotyping towards Africans – a history so long and loaded it stands apart from other contemporary fetishes, such as blondes or particular body types.

Why are black men willing to embrace the myths of hypersexuality and abnormally large endowment? “The number of things that have been said about black men in this country for the most part have been about as negative as you can possibly get,” says professor Herbert Samuels, an American expert on sexual desire. “If someone says that you are good at sex, or that your penis is bigger than anyone else’s, that’s about the only positive you can get out of all those negatives. And I think some black men have bought into the myth that they are hypersexual, that their sexual prowess and the size, the physicality, is greater.”

This is what really unsettles me about the Black Man’s Fan Club. Not just the fact that black men’s self-esteem could be so low that this would be a welcome boost, but the fact that everyone in Arousals is, one way or another, unquestioningly complicit in a set of beliefs that have ancient and horrible roots.

When Europeans first came into contact with the African continent, they indulged in an imaginative riot of fantasy. Elizabethan travel books contained a heady mix of fact and pure invention, which confused English readers and popularised wildly fictional versions of the place and its people. “Like animals,” one account reported, Africans would “fall upon their women, just as they come to hand, without any choice”. African men had enormous penises, these accounts suggested. One writer went so far as to claim that African men were “furnisht with such members as are after a sort burthensome unto them”.

Stereotypes about the sexual prowess of black people have an equally illustrious presence in literature, journalism and art. Even a left-leaning British publication like the Daily Herald ran front-page stories with headlines such as “Black scourge in Europe: sexual horror let loose by France on the Rhine”. The author of that 1920 splash complained that the “barely restrainable *******” of black troops stationed in Europe after the end of the first world war had led to many rapes, which was particularly serious because Africans were “the most developed sexually” of any race – a “terror and a horror unimaginable”.

Black men are still unfairly portrayed as rapists – not least by US president Donald Trump, who in 1989 called for the death penalty for five black teenagers, the so-called Central Park Five convicted of ******* a female jogger in New York. Their convictions were later overturned and the miscarriage of justice these young men had suffered exposed. But in 2014, Trump still refused to accept their innocence. He told a journalist this stance would help in his campaign for the presidency, and he found many receptive audiences for his racially loaded claim that Mexico was sending its “rapists” to America.

Stereotypes of black and other ethnic minority men as sexually threatening on the one hand, and sexually desirable on the other, are two sides of the same hypersexuality myth. The former continue in inaccurate data spread virally on social media, pointing to false statistics about the prevalence of sexual assaults by black men. The latter have filtered into popular culture, such as the sayings, widespread when I was at school and university, that white women who have sex with black men have “jungle fever”, and that “once you go black, you never go back”. They are implicit in the belief, internalised by Wayne at the BMFC, that black men have “extras” in bed."

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/jan/13/black-woman-always-fetishised-racism-in-bedroom

"Welcome to the Black Man’s Fan Club – a monthly swingers’ night for white women who want to have sex with black men, and their white husbands or partners who want to watch. In the ethnically undiverse world of swingers, the BMFC is marketed as a community of people who “appreciate the extras black men bring”. Tonight’s flyer features an intensely fake-tanned white girl wearing briefs that read, in large letters across her crotch, “I heart black”. Members of the community – both white women and black men – are active on Twitter, where they share pictures of exceptionally large black penises and rough sex in which a black man clearly dominates.

BMFC, the punters tell me, is one of a kind, but the sentiment doesn’t end in Dunstable. In an era of mass porn consumption, black male porn actors having sex with white women is a popular subgenre, and BMWW (black man white woman) erotic novels specifically cater to the fantasy of crudely stereotyped black male aggression and sexual domination. It’s as if the online commercialisation of sexual fantasy has globalised racial stereotypes and sent them freewheeling backwards; it doesn’t take any imagination to surmise exactly what swingers mean when they say they appreciate the “extras” black men bring.

“There are three reasons why the women come here,” explains Wayne, one of the black men who are here to be “appreciated”. Wayne has just come out of a playroom, and has barely bothered to put his clothes back on – his flies low, shirt open, and tie hung nonchalantly around his neck. He’s a good-looking guy, with a toned physique and neatly twisted locks. “One [reason is], black men have bigger penises.” That’s a stereotype, I argue. “It’s not a stereotype!” he replies. “Black men are built differently. You have to acknowledge nature. Number two,” Wayne continues, “black men have better rhythm in bed. That’s also a fact. And thirdly, they are just more dominant. You know, a lot of these women are not satisfied by their husbands, who want them to do all the work. They want to feel a strong man inside them, dominating them. They want an alpha male. That’s what they get here,” he smiles at me, knowingly.

[...]

When I ask if they feel fetishised because of their race, they vigorously deny it. “I come for the sex,” Wayne says. “Where else can you go and have sex as many times as you like? Plus, there are no pretences. Everyone is here to get laid, have a good time, it’s really friendly. It’s not like a normal club where everyone has a poker face on. No one’s judging.”

Swinging is not my thing, but I couldn’t care less what consenting adults get up to behind closed doors. It’s not the sex at the Black Man’s Fan Club that bothers me, it’s the racial stereotyping. It feels as if it’s just the latest chapter in a history of sexual stereotyping towards Africans – a history so long and loaded it stands apart from other contemporary fetishes, such as blondes or particular body types.

Why are black men willing to embrace the myths of hypersexuality and abnormally large endowment? “The number of things that have been said about black men in this country for the most part have been about as negative as you can possibly get,” says professor Herbert Samuels, an American expert on sexual desire. “If someone says that you are good at sex, or that your penis is bigger than anyone else’s, that’s about the only positive you can get out of all those negatives. And I think some black men have bought into the myth that they are hypersexual, that their sexual prowess and the size, the physicality, is greater.”

This is what really unsettles me about the Black Man’s Fan Club. Not just the fact that black men’s self-esteem could be so low that this would be a welcome boost, but the fact that everyone in Arousals is, one way or another, unquestioningly complicit in a set of beliefs that have ancient and horrible roots.

When Europeans first came into contact with the African continent, they indulged in an imaginative riot of fantasy. Elizabethan travel books contained a heady mix of fact and pure invention, which confused English readers and popularised wildly fictional versions of the place and its people. “Like animals,” one account reported, Africans would “fall upon their women, just as they come to hand, without any choice”. African men had enormous penises, these accounts suggested. One writer went so far as to claim that African men were “furnisht with such members as are after a sort burthensome unto them”.

Stereotypes about the sexual prowess of black people have an equally illustrious presence in literature, journalism and art. Even a left-leaning British publication like the Daily Herald ran front-page stories with headlines such as “Black scourge in Europe: sexual horror let loose by France on the Rhine”. The author of that 1920 splash complained that the “barely restrainable *******” of black troops stationed in Europe after the end of the first world war had led to many rapes, which was particularly serious because Africans were “the most developed sexually” of any race – a “terror and a horror unimaginable”.

Black men are still unfairly portrayed as rapists – not least by US president Donald Trump, who in 1989 called for the death penalty for five black teenagers, the so-called Central Park Five convicted of ******* a female jogger in New York. Their convictions were later overturned and the miscarriage of justice these young men had suffered exposed. But in 2014, Trump still refused to accept their innocence. He told a journalist this stance would help in his campaign for the presidency, and he found many receptive audiences for his racially loaded claim that Mexico was sending its “rapists” to America.

Stereotypes of black and other ethnic minority men as sexually threatening on the one hand, and sexually desirable on the other, are two sides of the same hypersexuality myth. The former continue in inaccurate data spread virally on social media, pointing to false statistics about the prevalence of sexual assaults by black men. The latter have filtered into popular culture, such as the sayings, widespread when I was at school and university, that white women who have sex with black men have “jungle fever”, and that “once you go black, you never go back”. They are implicit in the belief, internalised by Wayne at the BMFC, that black men have “extras” in bed."

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/jan/13/black-woman-always-fetishised-racism-in-bedroom

Last edited by a moderator:

)

)

you got coming by to have a great time with.

you got coming by to have a great time with.